Moving the Paddles - Keyboard Input - Demo 04¶

Objective¶

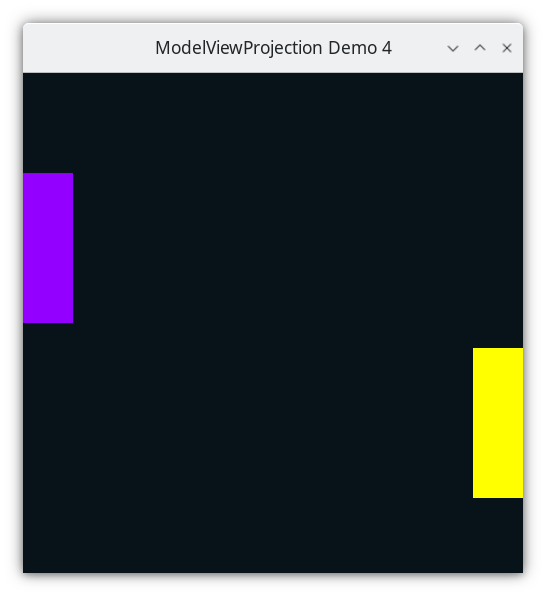

Add movement to the paddles using keyboard input.

Demo 04¶

How to Execute¶

Load src/modelviewprojection/demo04.py in Spyder and hit the play button.

Move the Paddles using the Keyboard¶

Keyboard Input |

Action |

|---|---|

w |

Move Left Paddle Up |

s |

Move Left Paddle Down |

k |

Move Right Paddle Down |

i |

Move Right Paddle Up |

Paddles which don’t move are quite boring. Let’s make them move up or down by getting keyboard input.

And while we are at it, let’s go ahead and create data structures for a Vector, and for the collection of vertices that make up a Paddle.

Code¶

Data Structures¶

Here we use dataclasses, which automatically creates on the class a constructor, accessor methods, and pretty-printer. This saves a lot of boiler plate code.

84@dataclasses.dataclass

85class Vector:

86 x: float

87 y: float

92@dataclasses.dataclass

93class Paddle:

94 vertices: list[Vector]

95 color: colorutils.Color3

Although Python is a dynamically-typed language, we can add type information as helpful hints to the reader, and for use with static type-checking tools for Python, such as mypy.

100paddle1 = Paddle(

101 vertices=[

102 Vector(x=-1.0, y=-0.3),

103 Vector(x=-0.8, y=-0.3),

104 Vector(x=-0.8, y=0.3),

105 Vector(x=-1.0, y=0.3),

106 ],

107 color=colorutils.Color3(r=0.578123, g=0.0, b=1.0),

108)

109

110paddle2 = Paddle(

111 vertices=[

112 Vector(0.8, -0.3),

113 Vector(1.0, -0.3),

114 Vector(1.0, 0.3),

115 Vector(0.8, 0.3),

116 ],

117 color=colorutils.Color3(r=1.0, g=1.0, b=0.0),

118)

Create two instances of a Paddle.

I make heavy use of keyword arguments in Python.

Notice that I am nesting the constructors. I could have instead have written the construction of paddle1 like this:

x = -0.8

y = 0.3

vector_a = Vector(x, y)

x = -1.0

y = 0.3

vector_b = Vector(x, y)

x = -1.0

y = -0.3

vector_c = Vector(x, y)

x = -0.8

y = -0.3

vector_d = Vector(x, y)

vector_list = list(vector_a, vector_b, vector_c, vector_d)

r = 0.57

g = 0.0

b = 1.0

paddle1 = Paddle(vector_list, r, g, b)

But then I would have many local variables, some of whose values change frequently over time, and most of which are single use variables. By nesting the constructors as the author has done above, the author minimizes those issues at the expense of requiring a degree on non-linear reading of the code, which gets easy with practice.

Query User Input and Use It To Animate¶

123def handle_movement_of_paddles() -> None:

124 global paddle1, paddle2

125 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_S) == glfw.PRESS:

126 for v in paddle1.vertices:

127 v.x += 0.0

128 v.y -= 0.1

129 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_W) == glfw.PRESS:

130 for v in paddle1.vertices:

131 v.x += 0.0

132 v.y += 0.1

133 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_K) == glfw.PRESS:

134 for v in paddle2.vertices:

135 v.x += 0.0

136 v.y -= 0.1

137 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_I) == glfw.PRESS:

138 for v in paddle2.vertices:

139 v.x += 0.0

140 v.y += 0.1

141

142

If the user presses ‘s’ this frame, subtract 0.1 from the y component of each of the vertices in the paddle. If the key continues to be held down over time, this value will continue to decrease.

If the user presses ‘w’ this frame, add 0.1 more to the y component of each of the vertices in the paddle

If the user presses ‘k’ this frame, subtract .1.

If the user presses ‘i’ this frame, add .1 more.

when writing to global variables within a nested scope, you need to declare their scope as global at the top of the nested scope. (technically it is not a global variable, it is local to the current python module, but the point remains)

The Event Loop¶

Monitors can have variable frame-rates, and in order to ensure that movement is consistent across different monitors, we choose to only flush the screen at 60 hertz (frames per second).

146TARGET_FRAMERATE: int = 60

147

148time_at_beginning_of_previous_frame: float = glfw.get_time()

152while not glfw.window_should_close(window):

153 while (

154 glfw.get_time()

155 < time_at_beginning_of_previous_frame + 1.0 / TARGET_FRAMERATE

156 ):

157 pass

158

159 time_at_beginning_of_previous_frame = glfw.get_time()

163 glfw.poll_events()

164

165 width, height = glfw.get_framebuffer_size(window)

166 GL.glViewport(0, 0, width, height)

167 GL.glClear(sum([GL.GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT, GL.GL_DEPTH_BUFFER_BIT]))

171 draw_in_square_viewport()

175 handle_movement_of_paddles()

We’re still near the beginning of the event loop, and we haven’t drawn the paddles yet. So we call the function to query the user input, which will also modify the vertices’ values if there was input.

179 GL.glColor3f(*iter(paddle1.color))

180

181 GL.glBegin(GL.GL_QUADS)

182 for vector in paddle1.vertices:

183 GL.glVertex2f(vector.x, vector.y)

184 GL.glEnd()

While rendering, we now loop over the vertices of the paddle. The paddles may be displaced from their original position that was hard-coded, as the callback may have updated the values based off of the user input.

When glVertex is now called, we are not directly passing numbers into it, but instead we are getting the numbers from the data structures of Paddle and its associated vertices.

Adding input offset to Paddle 1¶

188 GL.glColor3f(*iter(paddle2.color))

189

190 GL.glBegin(GL.GL_QUADS)

191 for vector in paddle2.vertices:

192 GL.glVertex2f(vector.x, vector.y)

193 GL.glEnd()

Adding input offset to Paddle 2¶

197 glfw.swap_buffers(window)