Rotations - Demo 07¶

Objective¶

Attempt to rotate the paddles around their center. Learn about rotations. This demo does not work correctly, because of a misunderstanding of how to interpret a sequence of transformations.

Demo 07¶

How to Execute¶

Load src/modelviewprojection/demo07.py in Spyder and hit the play button.

Move the Paddles using the Keyboard¶

Keyboard Input |

Action |

|---|---|

w |

Move Left Paddle Up |

s |

Move Left Paddle Down |

k |

Move Right Paddle Down |

i |

Move Right Paddle Up |

d |

Increase Left Paddle’s Rotation |

a |

Decrease Left Paddle’s Rotation |

l |

Increase Right Paddle’s Rotation |

j |

Decrease Right Paddle’s Rotation |

For another person’s explanation of the trigonometry of rotating in 2D, see

Rotate the Paddles About their Center¶

Besides translate and scale, the third main operation in computer graphics is to rotate an object.

Rotation Around Origin (0,0)¶

We can rotate an object around (0,0) by rotating all of the object’s vertices around (0,0).

In high school math, you will have learned about sin, cos, and tangent. Typically the angles are described on the unit circle, where a rotation starts from the positive x axis.

We can expand on this knowledge, allowing us to rotate all vertices, wherever they are, around the origin (0,0), by some angle \(\theta\).

Let’s take any arbitrary point

From high school geometry, remember that we can describe a Cartesian (x,y) point by its length r, and its cosine and sine of its angle \(\theta\).

Also remember that when calculating sine and cosine, because right triangles are proportional, that sine and cosine are preserved for a right triangle, even if the length sides are scaled up or down.

So we’ll make a right triangle on the unit circle, but we will remember the length of (x,y), which we’ll call “r”, and we’ll call the angle of (x,y) to be “\(\beta\)”. As a reminder, we want to rotate by a different angle, called “\(\theta\)”.

Before we can rotate by “\(\theta\)”, first we need to be able to rotate by 90 degrees, or \(\pi\)/2. So to rotate (cos(\(\beta\)), sin(\(\beta\))) by \(\pi\)/2, we get (cos(\(\beta\) + \(\pi\)/2), sin(\(\beta\) + \(\pi\)/2)).

Now let’s give each of those vertices new names, x’ and y’, for the purpose of ignoring details for now that we’ll return to later, just let we did for length “r” above.

Now forget about “\(\beta\)”, and remember that our goal is to rotate by angle “\(\theta\)”. Look at the picture below, while turning your head slightly to the left. x’ and y’ look just like our normal Cartesian plane and unit circle, combined with the “\(\theta\)”; it looks like what we already know from high school geometry.

So with this new frame of reference, we can rotate x’ by “\(\theta\)”, and draw a right triangle on the unit circle using this new frame of reference.

So the rotated point can be constructed by the following

Now that we’ve found the direction on the unit circle, we remember to make it length “r”.

Ok, we are now going to stop thinking about geometry, and we will only be thinking about algebra. Please don’t try to look at the formula and try to draw any diagrams.

Ok, now it is time to remember what the values that x’ and y’ are defined as.

A problem we have now is how to calculate cosine and sine of \(\beta\) + \(\pi\)/2, because we haven’t actually calculated \(\beta\); we’ve calculated sine and cosine of \(\beta\) by dividing the x value by the magnitude of the a, and the sine of \(\beta\) by dividing the y value by the magnitude of a.

We could try to take the inverse sine or inverse cosine of theta, but there is no need given properties of trigonometry.

Therefore

58@dataclasses.dataclass

59class Vector2D(mu1d.Vector1D):

60 y: float #: The y-component of the 2D Vector

82def rotate_90_degrees() -> mu.InvertibleFunction:

83 def f(vector: mu.Vector) -> mu.Vector:

84 assert isinstance(vector, Vector2D)

85 return Vector2D(-vector.y, vector.x)

86

87 def f_inv(vector: mu.Vector) -> mu.Vector:

88 return -f(vector)

89

90 return mu.InvertibleFunction(f, f_inv)

91

92

93def rotate(angle_in_radians: float) -> mu.InvertibleFunction:

94 r90: mu.InvertibleFunction = rotate_90_degrees()

95

96 def create_rotate_function(

97 perp: mu.InvertibleFunction,

98 ) -> typing.Callable[[mu.Vector], mu.Vector]:

99 def f(vector: mu.Vector) -> mu.Vector:

100 parallel: mu.Vector = math.cos(angle_in_radians) * vector

101 perpendicular: mu.Vector = math.sin(angle_in_radians) * perp(vector)

102 return parallel + perpendicular

103

104 return f

105

106 return mu.InvertibleFunction(

107 create_rotate_function(r90),

108 create_rotate_function(mu.inverse(r90)),

109 )

Note the definition of rotate, from the description above. cos and sin are defined in the math module.

85@dataclasses.dataclass

86class Paddle:

87 vertices: list[mu2d.Vector2D]

88 color: colorutils.Color3

89 position: mu2d.Vector2D

90 rotation: float = 0.0

a rotation instance variable is defined, with a default value of 0

118def handle_movement_of_paddles() -> None:

119 global paddle1, paddle2

120

121 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_S) == glfw.PRESS:

122 paddle1.position.y -= 1.0

123 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_W) == glfw.PRESS:

124 paddle1.position.y += 1.0

125 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_K) == glfw.PRESS:

126 paddle2.position.y -= 1.0

127 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_I) == glfw.PRESS:

128 paddle2.position.y += 1.0

129

130 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_A) == glfw.PRESS:

131 paddle1.rotation += 0.1

132 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_D) == glfw.PRESS:

133 paddle1.rotation -= 0.1

134 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_J) == glfw.PRESS:

135 paddle2.rotation += 0.1

136 if glfw.get_key(window, glfw.KEY_L) == glfw.PRESS:

137 paddle2.rotation -= 0.1

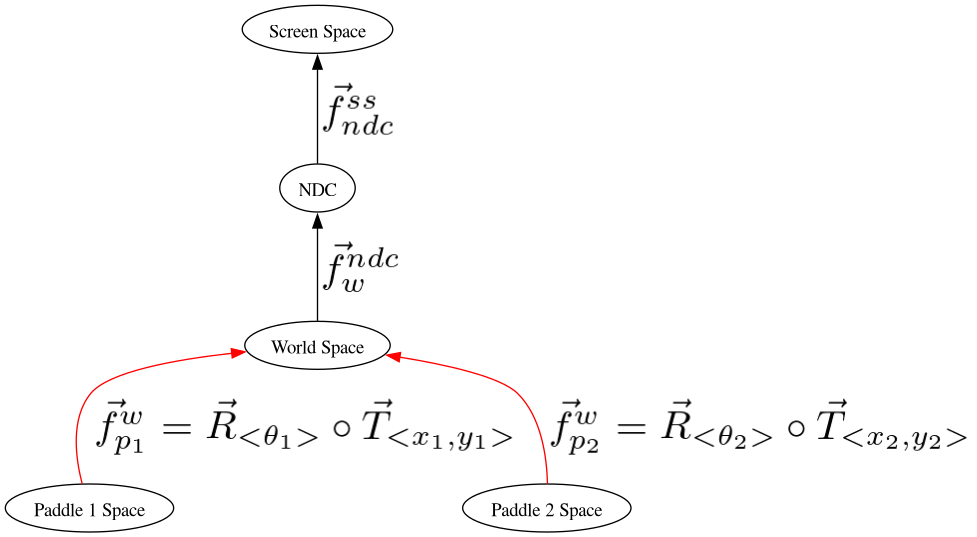

Cayley Graph¶

Code¶

The Event Loop¶

146while not glfw.window_should_close(window):

So to rotate paddle 1 about its center, we should translate to its position, and then rotate around the paddle’s center.

165 GL.glColor3f(*iter(paddle1.color))

166

167 GL.glBegin(GL.GL_QUADS)

168 for p1_v_ms in paddle1.vertices:

169 # doc-region-begin compose transformations on paddle 1

170 fn: mu2d.InvertibleFunction = mu2d.compose(

171 [

172 mu2d.uniform_scale(1.0 / 10.0),

173 mu2d.rotate(paddle1.rotation),

174 mu2d.translate(paddle1.position),

175 ]

176 )

177 paddle1_vector_ndc: mu2d.Vector2D = fn(p1_v_ms)

178 # doc-region-end compose transformations on paddle 1

179 GL.glVertex2f(paddle1_vector_ndc.x, paddle1_vector_ndc.y)

180 GL.glEnd()

...

Likewise, to rotate paddle 2 about its center, we should translate to its position, and then rotate around the paddle’s center.

184 GL.glColor3f(*iter(paddle2.color))

185

186 GL.glBegin(GL.GL_QUADS)

187 for p2_v_ms in paddle2.vertices:

188 fn: mu2d.InvertibleFunction = mu2d.compose(

189 [

190 mu2d.uniform_scale(1.0 / 10.0),

191 mu2d.rotate(paddle2.rotation),

192 mu2d.translate(paddle2.position),

193 ]

194 )

195 paddle2_vector_ndc: mu2d.Vector2D = fn(p2_v_ms)

196 GL.glVertex2f(paddle2_vector_ndc.x, paddle2_vector_ndc.y)

197 GL.glEnd()

Why it is Wrong¶

Turns out, our program doesn’t work as predicted, even though translate, scale, and rotate are all defined correctly. The paddles are not rotating around their center.

Let’s take a look in detail about what our paddle-space to world space transformations are doing.

170 fn: mu2d.InvertibleFunction = mu2d.compose(

171 [

172 mu2d.uniform_scale(1.0 / 10.0),

173 mu2d.rotate(paddle1.rotation),

174 mu2d.translate(paddle1.position),

175 ]

176 )

177 paddle1_vector_ndc: mu2d.Vector2D = fn(p1_v_ms)

See modelviewprojection.mathutils.compose

modelspace vertices

Translate

Reset the coordinate system

Modelspace¶

Rotate around World Spaces’s origin

Modelspace¶

Reset the coordinate system

Modelspace¶

Final world space coordinates

Modelspace¶

So then what the heck are we supposed to do in order to rotate around an object’s center? The next section provides a solution.